Because of Increased Immigration After the World Wars Became the Center for Developing Westerm Art

Abstract

In this chapter we outline the full general developments of migration within and towards Europe equally well every bit patterns of settlement of migrants. We provide a comprehensive historical overview of the changes in European migration since the 1950s. Main phases in immigration, its backgrounds, and its determinants across the continent are described making utilise of secondary literature and data. Different European regions are covered in the analyses, based on available statistics and an analysis of secondary fabric. This allows u.s. to distinguish betwixt different origins of migrants likewise every bit migration motives. In add-on to migration from outside Europe this chapter pays ample attention to patterns of mobility within Europe. The analyses comprehend the individual level with as much particular equally possible with the available statistics and specially take the demographic characteristics of migrants into business relationship. The analyses on flows of migration are supplemented by a sketch of the residing immigrant population across Europe.

Keywords

- European Wedlock

- Labour Migration

- European Union State

- Migration Catamenia

- Family unit Reunification

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

This chapter outlines the general developments of migration inside and towards Europe also as patterns of settlement of migrants since the 1950s. We take equally our starting point the bilateral labour migration agreements signed past several European countries in the 1950s and 1960s. Three main periods tin can be distinguished from this betoken onwards. The outset, upwards to the oil crisis in 1973–1974, was characterized by steady economical growth and evolution and deployment of guest worker schemes, (return) migration from former colonies to motherlands, and refugee migration, mainly dominated by movements from East to West. The 2d menstruum started with the oil crunch and ended with the fall of the Atomic number 26 Curtain in the belatedly 1980s. During this time N-Western European governments increasingly restricted migration, and migrants' main route of entrance became family reunification and family formation. Furthermore, asylum applications increased. By the cease of this period, migration flows had started to divert towards former emigration countries in Southern Europe. The 3rd menses is from the fall of the Iron Curtain until today, with increasing European Spousal relationship (European union) influence and control of migration from 3rd countries into the EU and encouragement of intra-European mobility.

The historical overview presented hither stems from a comprehensive literature report, complemented past an analysis of available statistical data for trends in the last decade. It should be noted, however, that statistical data on migration and mobility in Europe is mostly incomplete, as they are based mainly on reports and registrations of the individuals concerned. Besides, data on immigration and emigration are not always fully bachelor and are not consistently measured across countries and time (see, e.1000., EMN 2013). This means that the quality of migration data is often limited (Abel 2010; Kupiszewska and Nowok 2008; Nowok et al. 2006; Poulain et al. 2006). Several initiatives and projects accept been launched to overcome these problems and promote comparable definitions, statistics, and estimations of missing data (Raymer et al. 2011). Near of the EU's current 28 member countries produce almanac statistics on immigration and emigration. However, the data and level of detail is not yet comparable across countries (for an overview of databanks and limitations, run across Raymer et al. 2011). The last section of this chapter presents figures on migration and migrants relying mainly on data from iii enquiry projects which aimed to create and improve harmonized and consistent migration information (Abel and Sander 2014; Raymer et al. 2011, see world wide web.nidi.nl for more than data on the MIMOSA and IMEM projects). The decision summarizes the master patterns and discusses some implications of our findings.

Three Periods of Migration in Europe

From the 1950s to 1974: Invitee Worker Schemes and Decolonization

In the catamenia later the 2nd World War, North-Western Europe was economically booming. Industrial production, for example, increased by 30 % betwixt 1953 and 1958 (Dietz and Kaczmarczyk 2008). Native workers in this region became increasingly educated, and growing possibilities for social mobility enabled many of them to move up to white-collar piece of work (Boyle et al. 1998). Local workers could not fill the vacancies, every bit labour reservoirs were limited. Furthermore, the local native population was no longer willing to have upwardly unhealthy and poorly paid jobs in agriculture, cleaning, construction, and mining. Every bit a effect, North-Western European governments started to recruit labour in peripheral countries. The main destination countries were Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland. The recruited foreign workers were expected to return abode afterwards completing a stint of labour. They therefore tended to exist granted few rights and petty or no access to welfare support (Boyle et al. 1998). At the end of this period, most migrants in North-Western Europe originated from Algeria, Hellenic republic, Italia, Morocco, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia, Turkey, and Yugoslavia.

Initially, geographical proximity played an important role in the evolution of specific migration flows. For instance, Sweden recruited labour from Finland, the Great britain from Republic of ireland, and Switzerland from Italy. A migration system emerged whereby peripheral—especially Southern European—countries supplied workers to Due north-Western European countries. Migration flows were strongly guided by differences in economical evolution between regions characterized by pre-industrial agrarian economies and those with highly industrialized economies (Bade 2003; Barou 2006), both internationally and nationally (due east.g., with unskilled workers moving from Southern Italy towards the industrial centres in Northern Italy). Within the origin countries, most migrant workers were from poor agronomical regions where there was insufficient work, such equally Northern Portugal, Western Spain, Southern Italia, and Northern Greece (Bade 2003). However, European governments gradually enlarged their zones of recruitment to countries exterior Europe. I of the main reasons was the Cold War sectionalization of Europe which severely restricted East-W labour mobility. In West Germany, for example, in that location was a significant inflow of workers from Greece, Italia, and Spain, too every bit from Due east Germany. The structure of the Berlin Wall in 1961, however, put a stop to the latter. As a result, Due west Deutschland reoriented its recruitment towards elsewhere. Bilateral agreements were signed with Turkey (1961), Morocco (1963), Portugal (1964), Tunisia (1965), and Yugoslavia (1968). Other destination countries such as Belgium, holland, France, and Switzerland followed, as well signing labour migration agreements with these countries in the 1960s.

In this menstruation, international migration was generally viewed positively because of its economical benefits (Bonifazi 2008), from the perspective of both the sending and the receiving countries. In the Mediterranean region, for instance, emigration helped to alleviate pressures on the labour marketplace, every bit the region was characterized by pregnant demographic pressure, low productivity and incomes, and high unemployment (Page Moch 2003; Vilar 2001). A comparison of annual gross national product per capita in the 1960s illustrates this with US $353 for Turkey, $822 for Spain, and $1272 for Italy; $1977 for the United kingdom and $2324 for France (Page Moch 2003, 180). Furthermore, migrants' remittances were expected to benefit the national economy. In Turkey, for example, the monetary returns of migrants became a vital element of the economy: the land even experienced economic destabilization when labour migration to Germany ended in 1974 (Barou 2006). However, reasons for origin countries to support emigration went across the economical. The Italian government, for case, considered the labour migration programmes of North-Western European countries every bit a way to 'get rid of the unemployed and to deprive the socialist and communist parties of potential voters' (Hoerder 2002, 520).

Estimates of the numbers of individuals that left Italian republic, Spain, Greece, and Portugal between 1950 and 1970 vary from 7 to x million (Okólski 2012). As can be seen from Table iii.i, in 1950 immigrant populations were nigh numerous in France, the Uk, Deutschland, and Belgium.

Twenty years afterward, at the beginning of the 1970s, these numbers had increased substantially in both absolute and relative terms (Table 3.ane). One in vii transmission labourers in the UK and one in four industrial workers in Belgium, France, and Switzerland were of foreign origin in the mid-1970s (Folio Moch 2003, not in table). Eighty per cent of the full foreign stock in 1975 was concentrated in four countries, namely French republic, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK (Bonifazi 2008).

At the same time, the process of decolonization gave ascent to considerable migration flows towards Europe's (erstwhile) colonial powers. A significant number of people from the colonies came to Belgium, France, the Netherlands, the Great britain, and in the 1970s, Portugal. Many of these (return) migrants were juridically considered citizens; estimates suggest that betwixt 1940 and 1975 the number of people of European origin returning from the colonies was around 7 meg (Bade 2003). The main (return) migration flows were from Republic of kenya, Republic of india, and Malaysia to the UK, from Northern Africa to France and Italy, from Congo to Belgium (although in smaller numbers), and from Indonesia to the Netherlands (Bade 2003). Some of these migrants, equally for example from the new Commonwealth, came for economic reasons (Folio Moch 2003). Others, such as the Algerian harkis (auxiliaries in the French colonial army) in French republic, Asian Ugandans in Britain, and a substantial share of Surinamese in kingdom of the netherlands, arrived during or afterward independence (ibid.). In the 1970s, Portugal received a meaning number of citizens "returning" from its former colonies, fleeing from violent combats in the struggle for independence. Although European migrants returning from the colonies were often quickly able to insert themselves into the social fabric of the mother land, this was less the case for those of non-European origin who were economically and socially deprived and also frequently discriminated (Bade 2003).

Lastly, the Atomic number 26 Mantle severely limited East-West mobility. Nevertheless, information technology did not bring East-West migration to a consummate halt (Fassmann and Münz 1994). Straddling our period demarcations we discuss these migrations patterns here, as they started in this catamenia. Between 1950 and 1990, 12 million people migrated from East to West (Fassmann and Münz 1992), many of them to Germany. Between 1950 and 2004, for example, 4.45 million Aussiedler—ethnic Germans from Central and Eastern Europe—returned to Germany (Dietz 2006). Until 1988, most of these Aussiedler migrated from Poland (Dietz 2006; Münz and Ulrich 1998). Nevertheless, the largest share of these Aussiedler (63 %) arrived after 1989 (Dietz 2006). The vast bulk who came afterward the fall of the Fe Drapery originated from the sometime Soviet Union (Dietz 2006; Münz and Ulrich 1998). Occasionally, still, there were larger inflows of Eastern Europeans, following political crises such every bit from Hungary (1956–1957), Czechoslovakia (1968–1969), and Poland (1980–1981) (Castles et al. 2014; Fassmann and Münz 1992, 1994). In line with the logic of the Cold War, whatsoever the motives of those who moved to the W, they were considered to be political refugees (Fassmann and Münz 1994).

From 1974 to the End of the 1980s: The Oil Crisis and Migration Control

The oil crunch of 1973–1974 had considerable impact on the economic landscape of Europe. The crunch gave impetus to economic restructuring, sharply reducing the need for labour (Boyle, Halfacree & Robinson 1998). During this period, conventionalities in unbridled economic growth diminished. Switzerland and Sweden were the first countries to invoke a migration stop, respectively, in 1970 and 1972. Others followed: Frg in 1973 and the Benelux and France in 1974. Policies aiming to command and reduce migration, however, transformed rather than stopped migration. The number of strange residents kept rising, due to a change in European migration systems from circular to chain migration and the related natural growth of migrant populations. Migrants from non-European countries who had come under labour recruitment schemes increasingly settled permanently, every bit returning to their abode country for long periods now entailed a significant risk of losing their residence permit. Many migrants started to bring their families to Europe. Although governments initially tried to limit family migration, this met petty success (Castles et al. 2014; Hansen 2003). After all, family unit reunification of migrant workers was considered a key right, anchored in commodity 19 of the European Social Lease of 1961.

The composition of the residing migrant population likewise changed during this period. Whereas in the get-go period, European migrants were most numerous, the share of not-European migrant populations significantly grew during the second menses. In Sweden, for example, xl % of the strange born were non-European by 1999, compared to only 7.6 % in 1970 (Goldscheider et al. 2008). This reflected the continuing immigration and natural growth of these populations. But information technology was too the result of a larger extent of render migration among Southern European populations, given the increased quality of life and employment opportunities in Southern Europe (Barou 2006). In countries on the other side of the Mediterranean, population force per unit area continued to be substantial, due to high fertility and unemployment rates. During this menstruation, the number of Greek, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Yugoslavian foreigners in Europe macerated (except in Switzerland, where the number of Portuguese and Yugoslavians grew), and a significant increase was observed in the number of Turks and Due north Africans across Europe (Bade 2003).

After the migration stop, countries increasingly controlled entries of foreigners, and migration became an important topic in national political and public debates (Bonifazi 2008; see also Doomernik & Bruquetas in this volume). Increasing unemployment levels due to the economical recession fuelled hostility, racism, and xenophobia towards certain "visible" groups of resident migrants. In several European countries, violent anti-foreigners incidents occurred. In France, for case, Le Pen's Forepart National acquired considerable political back up for its unproblematic bulletin that '2 million unemployed = two meg immigrants as well many' (Boyle et al. 1998, 27). During this catamenia, still, sensation also grew that immigrant populations were here to stay. Equally a result, the need for adequate integration policies became apparent, and such policies slowly started to develop (see Doomernik and Bruquetas in this book).

In this aforementioned phase, numbers of asylum applications started to rise in Europe (especially in the 1980s and after the autumn of the Berlin Wall; Hansen 2003). Between the early 1970s and the end of the twentieth century the number of aviary applications in the EU, at that time 15 fellow member states, increased from 15,000 to 300,000 annually (Hatton 2004). Germany was the largest recipient of asylum applications in Europe in all periods (Table 3.2). From the 1980s onwards, significant increases were also observed in Kingdom of belgium, holland, and the UK. The unlike attractiveness of particular European countries over fourth dimension is related to historical events that accept induced new refugee flows. The dramatic increase in asylum applications from within Europe in the early 1990s, for example, accompanied the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the Yugoslavian wars (Hatton 2004, run across besides further on in this affiliate).

The restrictions on the entrance of foreigners into Northward-Western Europe also had another issue. From the mid-1980s onwards, migration flows increasingly diverted towards Southern Europe, specially gaining momentum in the 1990s. Hellenic republic, Italy, Portugal, and Spain had long been emigration countries. Equally a event, they did not dispose of well-developed clearing legislation and archway control systems. Furthermore, these countries were experiencing economic growth and falling birth rates, resulting in labour shortages (Castles et al. 2014). The jobs available were often irregular ones, characterized by unfavourable labour conditions and low pay, making them unattractive to the local population. Southern Europe thus became an bonny destination for non-European migrants, especially those from North Africa, Latin America, Asia, and—afterwards the fall of the Iron Mantle—Eastern Europe (Castles et al. 2014).

Besides migration flows from non-European countries, the favourable economic conditions in Southern Europe also resulted in return migration among those who had moved to Northern Europe. Spain, for example, registered the return of 451,000 citizens during this period, of which 94 % had resided in another EU land (Barou 2006). Portugal, in dissimilarity, experienced return migration from its former colonies, where violent and violent struggles for independence were under mode. Greece was the terminal country to transition from an emigration into an immigration country. Until 1973, some 1 million Greeks were working abroad (Bade 2003). Half of them returned in the period after the oil crisis (ibid.).

From the 1990s to 2012: Recent Trends in Migration towards and Within Europe

Patterns of migration from, towards, and within Europe underwent significant changes and further diversification starting in 1990. The collapse of the Fe Curtain and the opening of the borders of Eastern Europe induced new migration flows across Europe. The end of the Common cold War, as well as the wars in the former Yugoslavia led to new flows of asylum seekers to Western Europe. Between 1989 and 1992, for example, aviary applications increased from 320,000 to 695,000, to decline to 455,000 by the stop of the decade (Hansen 2003) and increment again to 471,000 in 2001 (Castles et al. 2014). The peak-five countries of origin during this period were the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (836,000), Romania (400,000), Turkey (356,000), Iraq (211,000), and Afghanistan (155,000) (ibid.). In the first decade of the xx-start century, new asylum applications followed the conjuncture of admission restrictions and numbers of violent conflicts (ibid.). Between 2002 and 2006, aviary applications in the EU-15 decreased from 393,000 to 180,000 (ibid.). From 2006 onwards, however, aviary applications rose due to the conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and more than recently, the Arab Spring. Past 2010, the EU-25 plus Kingdom of norway and Switzerland had received 254,180 applications, and humanitarian migration accounted for half-dozen % of newcomers to the European union (ibid.). Almost applications were fabricated in France (47,800), Germany (41,300), Sweden (31,800), the United kingdom (22,100), and Kingdom of belgium (nineteen,900) (OECD 2011, Table A.i.3., cited in Castles et al. 2014, 229).

The 1992 Maastricht Treaty's abolition of borders considerably eased intra-European union movements (see also next sections of this chapter). At the same time, entrance into the EU became progressively restricted due to the unification of the European market place, which imposed strict edge controls and visa regulations. These controls on the entrance of foreigners went mitt in hand with increased irregular migration (Bade 2003; Bonifazi 2008; Castles et al. 2014). Migrants' countries of origin as well as their migration motives became increasingly diversified.

[Present migrants] come up to Europe from all over the world in significant numbers: expatriates working for multinational companies and international organizations, skilled workers from all over the world, nurses and doctors from the Philippines, refugees and asylum seekers from African, near Eastern and Asian countries, from the Balkan and former Soviet Union countries, students from Cathay, undocumented workers from African countries, simply to single out some of the major immigrant categories (Penninx 2006, eight).

During this third period, integration bug became a central policy concern (see Doomernik & Bruquetas in this volume). Many European countries stepped up attempts to attract highly skilled or educated migrants. This goal is still reflected in a number of national programmes today, for instance, in Denmark, Deutschland, Sweden, and the United kingdom. The EU established its Blue Card Scheme, an European union-wide residence and work let (Eurostat 2011). Moreover, educatee migration from outside the Eu became increasingly important in some parts of the European union (ibid.). Some countries' governments have actively recruited students with the intention of incorporating the "best and brightest" into their domestic labour market upon graduation (Lange 2013). Institutions of higher pedagogy accept joined these efforts, stimulated by the economic benefits of alluring international students in the grade of high tuition fees (Findlay 2011). In this context, several European countries, such as France, Frg, holland, and the U.k. simplified procedures for international students to make the instruction-to-work transition (Tremblay 2005; Van Mol 2014).

In the terminal section of this chapter, we differentiate between intra-EU mobility of European citizens and migration inside and towards the EU of tertiary-land nationals, every bit these groups are subject to dissimilar legislation. Intra-European mobility is often considered in positive terms, as contributing to the European union's 'vitality and competitiveness' (e.g., EC 2011, 3–iv). European citizens, moreover, are entitled to motility freely within the EU without the demand for a visa, and hence may face up fewer institutional barriers in migration trajectories. Migration into the European union, in contrast, remains largely associated with active measures of admission restriction and border control (see, e.g., Quango of the Eu 2002). In recent decades, European migration policy has thus represented 'different intersecting regimes of mobility that normalise the movements of some travellers while criminalising and entrapping the ventures of others' (Glick Schiller and Salazar 2013, 189). The global economic crisis that started in 2008 might be considered the end of this third flow, as it brought, at least temporarily, an end to 'rapid economic growth, European union expansion and high immigration' (Castles et al. 2014, 103). Even so, equally Castles, De Haas and Miller (ibid.) observe, the decline in clearing from non-European countries has been rather modest, and the anticipated mass returns to migrants' home countries have not occurred as even so. The crunch mainly seems to have affected intra-European migration, with a decrease in overall free movement within the European union and with the peripheral countries hardest hit by the crisis—specially Hellenic republic, Ireland, Italian republic, Portugal, and Spain—again becoming emigration countries (Castles et al. 2014).

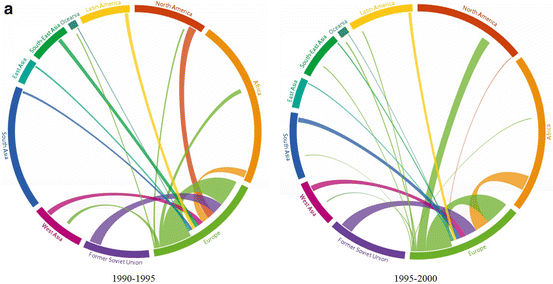

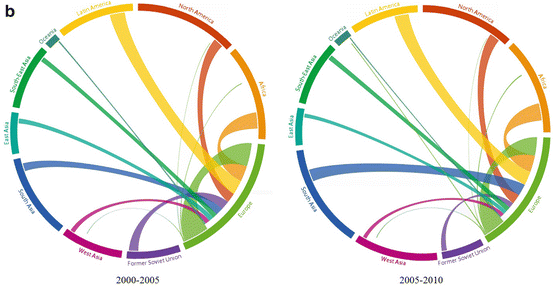

Migration Towards and from Europe

We first analyse general trends in migration towards Europe, based on new estimates of global migration flows by Abel and Sander (2014). Their figures are based on stock statistics published by the United Nations. Note, still, that using stock data might be misleading for measuring flows. Furthermore, although the tables below correspond the all-time estimates available, they are far from complete, as they are based on national statistics and thus reflect different legislation and definitions. This causes, for example, difficulties in comparability betwixt countries as well as over fourth dimension. The presented figures should thus be seen every bit indicative of larger patterns. The round plots nowadays migration flows from dissimilar earth regions towards Europe and vice versa (Fig. 3.i) for four five-year periods between 1990 and 2010. Broader lines betoken more sizeable migration flows, while the arrow indicates the direction of the menstruation. Every bit tin be observed, migration from sometime Soviet Wedlock countries to Europe gained momentum after the autumn of the Berlin Wall merely gradually decreased thereafter. Migration from Africa to Europe increased, especially in the mid-1990s. Furthermore, migration from East, South, and South-Due east Asia and from Latin America significantly rose, particularly after the start of the twenty-first century. Finally, migration from North America, Oceania, and West Asia remained relatively stable. Additional Eurostat data (not in the plots) evidence that betwixt 2009 and 2012, the influx of not-EU migrants into the EU decreased slightly, from 1.4 million in 2009 to ane.two 1000000 in 2012 (Eurostat 2014a).

Circular plots of migration flows towards and from Europe, per 5 yr period betwixt 1990 and 2010 (Source: www.global-migration.info)

In terms of the stock, four % of the full European union population in 2013 was a not-EU national, accounting for about 6 % of the Eu'south total working historic period population (Eurostat 2014a). Not-EU nationals were evenly split up between men and women (ibid.). Note, however, that these data by nationality do not include all foreign-origin European residents (meaning those born abroad or having a strange-born parent), as they cover only those who did not hold the nationality of the country they resided in. We further deconstruct these general trends below with a main focus on the last decade.

Looking at the height-15 countries of origin of newly arrived immigrants in 2009 and 2012, we find large numbers of migrants from Republic of india and People's republic of china, followed by Morocco and Pakistan (Table 3.iii). Based on figures from 2008, the majority of Indian and Pakistani migrants seems to have headed to the Britain. Nearly Chinese migrants seem to take gone to Espana (Eurostat 2011), and Moroccan migrants were mainly attracted to Italy and Spain.

In addition to the data on newly arriving immigrants (catamenia statistics), it is also relevant to know the chief countries of origin of non-European migrants residing in the Eu (stock statistics). When considering the acme-10 countries of origin of not-European union nationals residing in the EU (Table iii.4), it can be noted that the largest residing populations are from countries where Europe recruited labour in the mail service-state of war flow (Morocco and Turkey), as well as from one-time colonies (India and Pakistan), and countries virtually the European union's eastern border (Republic of albania, Russia, and Serbia). The large Chinese diaspora is also prominent as well as the—more often than not highly-skilled and lifestyle (Castles et al. 2014)—migrants from the The states.

Until the 1990s, the vast majority of migrants could conveniently exist classified under the categories "family reunification", "labour migration", and "asylum". Since the 1990s, nonetheless, migration motives have become increasingly diversified, including a growing number of immature people migrating to attend higher educational activity. Co-ordinate to Eurostat (2014a), in 2012, 32 % of migrants received a residence permit for family unit reasons, 23 % for work, 22 % for education, and 23 % for other reasons including asylum. Moreover, it should be noted that these categories written report merely the chief migration motive as captured in the official statistics. In practise, these categories reflect migration motives every bit accustomed in admission labels. Both may shift in the form of time. International students, for example, might go labour migrants upon graduation, and afterwards seek family reunification.

Lastly, migration is often not limited to moving from Country A to Country B but may involve several successive destinations. Because intra-EU mobility of third-country nationals, an upward trend is observed between 2007 and 2011. This trend is most prominent in Deutschland, where the number of third-country nationals arriving from European Economical Expanse countries more than tripled, from 3784 in 2007 to eleven,532 in 2011 (EMN 2013). A similar ascent is also observed in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, where numbers increased from 1000 to 3000 (ibid.). Increases seem to be more modest in other Eu countries, such every bit Austria (33.6 %), Finland (17.one %), the Netherlands (53.vii %), and Sweden (30.2 %) (ibid.). All the same, whereas these percentages are high, absolute numbers are more often than not depression. Compared with European citizens, intra-EU moves of third-land nationals are establish to form but a small share of total intra-EU mobility between 2007 and 2011. The share of non-European union nationals in these movements barely surpasses four % in the countries for which statistics are available: 1.eight % in Frg, iii.six % in Austria, 3.vii % in Finland, 2.3 % in the Netherlands, and i.ii % in the United kingdom (ibid.). Tertiary-country nationals, moreover, move to geographically shut countries, for example, from Federal republic of germany and Italy to Republic of austria, from Estonia and Sweden to Republic of finland, from the Czechia and Federal republic of germany to Poland, from Republic of austria and the Czechia to Slovakia, and from Denmark and Federal republic of germany to Sweden (ibid.). In sum, although it is oft assumed that linear migration trajectories between 2 countries are less common now (see, e.g., Pieke et al. 2004), non-EU migrants practise not seem to move oftentimes within the European union. This might be due to the legal restrictions oft imposed on this group of migrants, or information technology could be more than related to factors such as linguistic communication similarities between bordering countries (De Valk and Díez Medrano 2014).

Mobility of European union Citizens

Numbers and Destinations

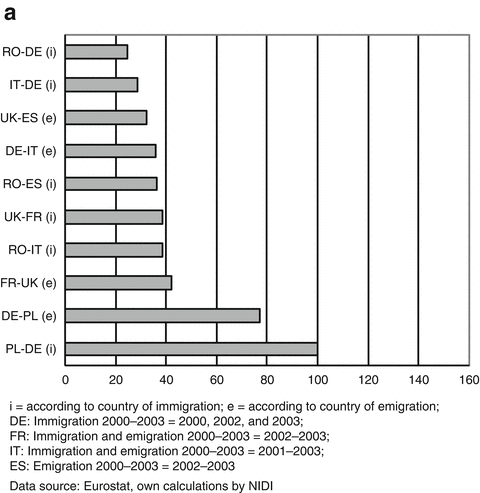

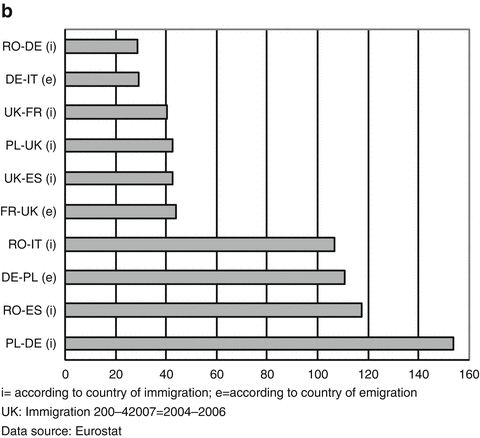

Previous studies betoken that merely a small share of the European population is mobile (Bonin et al. 2008; Pascouau 2013). Favell and Recchi (2009), for example, show that less than 1 in fifty Europeans lives away, and effectually 4 % have some experience of living and working abroad. However, the scale of intra-EU mobility clearly increased between 2000 and 2011 (Fig. 3.two). Data from Eurostat (2011), for example, prove that most 2 million EU citizens moved within the European union in 2008. In absolute numbers, Smoothen migration fabricated upward the greatest share of intra-Eu flows in the first decade of the twenty-first century (Fig. iii.ii). Migration between Poland and Deutschland was most prevalent, and consists of movements from as well as to Poland. The prevalence of Polish-German migration might be explained by the fact that such migration has been regulated since 1990, when the High german and Smoothen governments signed a bilateral understanding allowing Polish citizens to engage in legal seasonal employment for 3 months in specific sectors of the German economy (Dietz and Kaczmarczyk 2008). This led to a sharp increment in the inflow of Polish seasonal workers in Germany, from approximately 78,600 in 1992 to 280,000 in 2002 (ibid.). From 2004 to 2007, later Poland's European union accession, we observe a similar increase in population movements from Poland to the United kingdom. This tin can exist attributed to the fact that—unlike other EU member states—Ireland, Sweden, and the UK did non restrict migration from the new member states. Of these three destinations, Republic of ireland and the UK were the nigh pop, in part due to favourable labour market atmospheric condition (Castles et al. 2014). In more than recent years, however, many Smooth migrants have left the U.k., indicating increasing render migration, perhaps related to the economic crisis, as the Polish economy has kept growing (Castles et al. 2014). Apart from the migration flows from and towards Poland, similar inflows and outwards movements from Romania were observed between 2000 and 2011. Whereas between 2000 and 2003 some 39,000 Romanians migrated to Italia and Espana, these numbers increased to about 110,000 in the subsequent years. Furthermore, Romanian migration to Italy remained relatively stable, in sharp contrast with the migration flow towards Spain, which dropped sharply between 2008 and 2011. This tin can be attributed to the more difficult labour market place conditions in Spain, because of the economic crisis, which has redirected the move of Romanian migrants towards other Eu countries (OECD 2013).

Top-ten intra-European migration flows, 2000–2011 (absolute numbers)

Too migration between Eastern Europe and several other European union countries, migration flows have been considerable betwixt the Britain, France, and Espana. These movements likely include retirement migration from Northern to Southern Europe, but also point to increased labour mobility between these countries, peculiarly considering the flows towards the UK, as will be farther discussed later.

Finally, in recent years, the global economical crunch seems to have impacted patterns of intra-EU migration. Information from the OECD (2013) testify, for instance, an increase in emigration from countries heavily affected by the crunch (Table iii.5). Cases in point are Hellenic republic and Spain where unemployment rose to unprecedented levels—27.iii % in Hellenic republic and 26.1 % in Spain in 2013, with youth unemployment rates of, respectively, 58.iii and 55.v % that same year (Eurostat 2014b). Countries that eased their way into economic recovery, such as Iceland and Ireland, take already registered declines in the numbers of individuals leaving these countries (OECD 2013). Belgium, Deutschland, the Netherlands, and the UK appear to be popular destination countries, as intra-European migration flows towards these countries almost doubled in the five years prior to 2012. The crisis, however, also led to migration to non-European countries, such as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, Turkey, the USA, and in the example of Portugal, to quondam colonies in Africa (Castles et al. 2014).

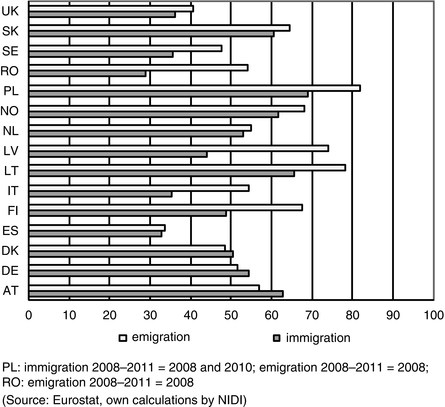

It is of import to go on in mind that most of the previous analyses are based on accented numbers, whereby EU member states with larger populations are logically more visible. We now consider the relative importance of migration flows as a share of countries' total immigration and emigration figures. Effigy 3.three shows the relative share of EU migration for selected European union countries.

Share of intra-European migrants in total emigration and immigration for selected European countries, 2008–2011 (%)

Intra-EU migration forms a substantial share of movements to and from the bulk of the countries in Fig. 3.3. Based on these numbers, we tin can discern several groups. The commencement group consists of countries where intra-EU clearing and emigration comprises the largest share of migration movements. It includes Austria, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, and Denmark. The attraction of these countries is explained by their well-adult economies. Particularly pregnant within this group are Shine and Lithuanian migrants moving on to other European destinations. The second group is fabricated up of countries where more than than one-half of emigration moves are directed towards other European countries, and clearing is mostly non-European. This group is comprised of Republic of finland, Italy, Latvia, and Romania. Their geographical location at the borders of Europe might explain this design, as these countries receive immigrants from neighbouring (non-European) countries and role equally transit countries. Furthermore, these countries might be less attractive to migrants from other EU countries because of their limited economic opportunities and relatively low wages (except for Finland). The third grouping consists of countries where both emigration and immigration from and to non-European countries is nonetheless of considerable importance. This group includes Spain, Sweden, and the U.k.. For Sweden, the most pop destinations for migrants are (besides the Nordic neighbours) English-speaking countries such equally the UK and the U.s. (Mannheimer 2012). In terms of the arriving population, humanitarian refuge and family reunification are the main channels of clearing in Sweden, which explains the large share of non-European migrants (Fredlund-Blomst 2014). Spain's and the UK'south migration balances might reflect continuing migration from former colonies and historical links with various world regions which include, for example, language similarities. The Great britain attracts a considerable number of migrants from ex-colonies such every bit India and Islamic republic of pakistan (Office for National Statistics 2011). Furthermore, the principal non-European destinations for UK migrants are English-speaking countries such as Commonwealth of australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the USA (Murray et al. 2012). For Spain, not-European migrants mainly originate from Kingdom of morocco and Latin American countries, and Spanish migrants emigrate to Latin American countries such equally Argentina and Venezuela (INE 2014).

Demographic Characteristics of Intra-EU Movers

It has been suggested that free movement within the EU is specially availed of past the highly educated (Favell 2008). Nosotros therefore investigate the demographic characteristics of those who move within Europe, focusing on selected cases and the period 2008–2011. Contrasting these cases, for which nosotros have detailed information, suggests the multifariousness of migration flows and motives within Europe. Obviously this analysis does not practice justice to more contempo moves from Southern Europe to North-Western Europe, only information to make like analyses are not notwithstanding at hand.

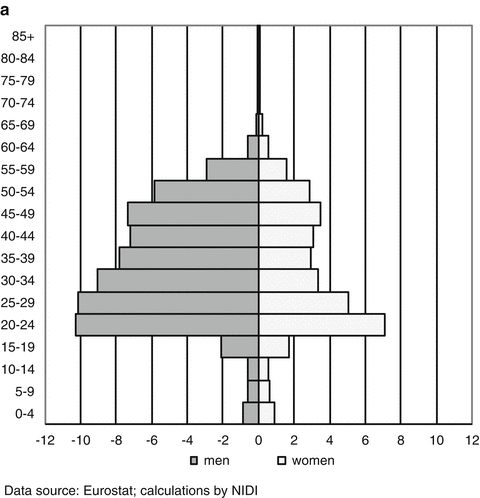

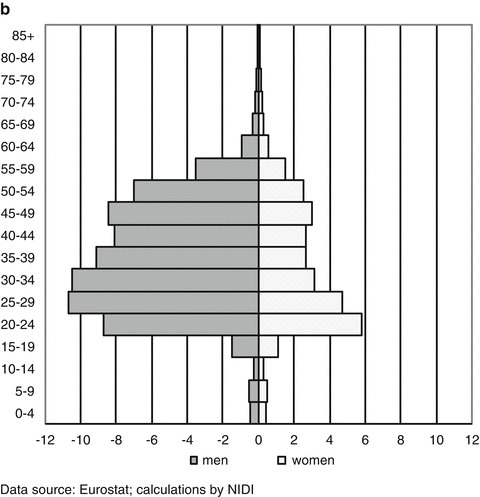

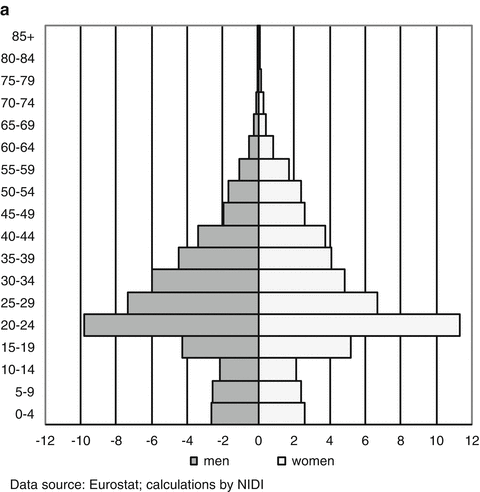

Nosotros start with characteristics of those who motion. Effigy 3.4 shows population pyramids for Polish migrants heading to Germany and vice versa. As we demonstrated previously (run across Fig. 3.2), Polish-German migration is the nearly prominent intra-European migration flow in absolute numbers. The population pyramids are indicative of the trend in the preceding years. Mobility between both countries is clearly dominated past men, particularly those between 20 and 50 years of age. This strongly male-dominated movement of Polish workers towards Germany appears temporary, equally a similar population moves back again (compare Fig. iii.4a and b).

Population pyramid of migrants from Poland to Frg (a) and Germany to Poland (b), 2008 (%)

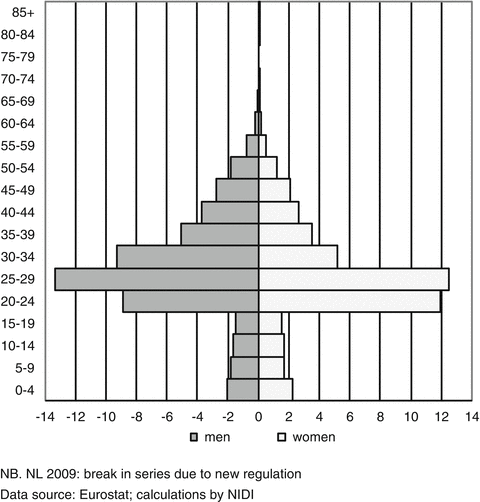

When we compare Shine migration to Germany with Polish migration to the netherlands, we notice a different panorama (Fig. 3.5). Polish migrants in the netherlands are significantly younger, the majority being between 20 and 35 years of age. Moreover, at that place is a more than equal gender residual. The coincidence of these migration flows with other life transitions, such as having children and forming a union, is crucial to gain insight into the way intra-European mobility develops over the life grade.

Population pyramid of Smooth migrants to the Netherlands, 2009 (%)

Recent research on Polish migrants based on Dutch population registers shows that having children also equally the choice of partner are important determinants of permanent settlement (Kleinepier et al. 2015). Like findings take been reported on intra-EU migrant groups in other destinations such as Kingdom of belgium and the Britain (see, eastward.1000., Levrau et al. 2014; Ryan and Mulholland 2013). Where generally circular and return migration of intra-European union movers is loftier, this seems especially so for those who are young, single, and practise non have children (run across, e.g., Bijwaard 2010; Braun and Arsene 2009; Kleinepier et al. 2015; Nekby 2006).

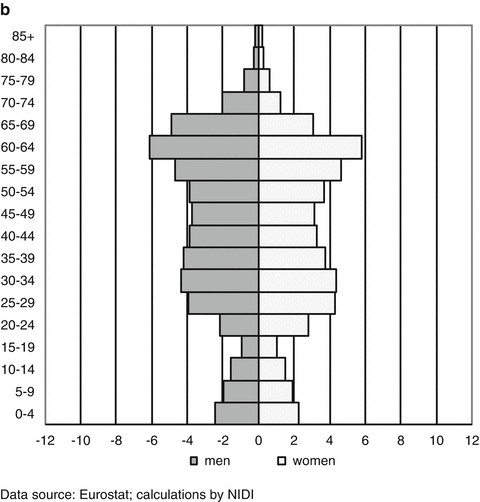

The relationship between life grade and migration becomes more apparent when we compare migrants from Romania and those from the UK residing in Spain (Fig. three.half-dozen). Romanian migration to Spain is conspicuously dominated by young people, with an overrepresentation of the 20–24 year category. Most of these men and women arrived in Kingdom of spain for work or study. The population pyramid of British residents in Spain has a totally different structure. Some of the British migrants are 30–xl years erstwhile, and many are in the older age groups, from 55 years and older. Thus, British migrants in Espana seem to be free movers coming to piece of work in Spain alongside retirement migrants.

Population pyramid of Romanian (a) and British (b) migrants in Spain, 2008–2011 (%)

In sum, patterns of intra-EU migration are becoming increasingly diverse. European citizens savor the correct of freedom of movement, and might decide to temporarily or permanently settle in another European country for a variety of reasons, including family formation, retirement, study, and piece of work. Finally information technology is crucial to realize that categorization of migrants into sure migration motives is rather difficult as very oft multiple different reasons overlap (run into, e.grand., Gilmartin and Migge 2015; Santacreu et al. 2009; Verwiebe 2014).

Conclusions

In this affiliate we addressed the offset key player of the binomials presented in Chap. 1 of this volume, namely migrants themselves. We offset of all presented a historical overview of trends in international migration to and within Europe since the 1950s. Furthermore, we examined the demographic characteristics of these migration flows besides as the characteristics of residing migrants across Europe using contempo information. We looked at both clearing and emigration in the European context to practise sufficient justice to the dynamic nature of migration. Nevertheless, our findings provide only a general overview, every bit the complexity of migration to and from Europe extends well across the telescopic of a single chapter. 3 historical periods were distinguished. Information technology is of import to deport these different periods in listen when studying current migration flows in Europe. They help to frame but also for analysing the (demographic) behaviour of migrant populations. The distinguished periods may help us to structure and sympathise the socio-demographic situations which migrants face today. In improver, this stardom into different periods enables us to capeesh the current and ongoing political and public debates on migration in Europe.

The first menstruum was characterized by labour migration and a favourable stance towards migration, roofing the years from the starting time of the bilateral guest worker agreements until the oil crisis. European governments first recruited guest workers in Southern Europe, just chop-chop expanded towards countries at Europe'due south borders. Apart from labour migration, a meaning postcolonial migration menstruum characterized this period. Due to struggles for independence in onetime colonies, many European countries received return migrants as well every bit migrants fleeing hostile disharmonize environments. The Common cold War limited East-West mobility during this period.

The 2nd flow extended from the oil crisis in the early 1970s to the autumn of the Fe Mantle in the late 1980s. It was characterized by a cessation of guest worker migration and stringent entry restrictions for new migrants. Nevertheless, migration flows were transformed rather than halted. Whereas previously labour migration had been the chief migration channel, family unit reunification (and family formation) at present took over the primary function, and asylum applications were too on the rising. European governments became aware that migrant populations were likely to remain on their territory, and they slowly began to develop integration policies. This continues to be an important consequence in the soapbox today.

The third menses dates from the 1990s to the nowadays day. During this fourth dimension, we discover substantial diversification in terms of countries of origin, destinations, flows, migration motives, and construction of migrant populations. One of the most of import elements in this menstruum has been the removal of barriers to intra-European mobility, while migration into the EU has go more restricted. As such, intra-EU mobility and migration into the EU accept become embedded in different and often opposing discourses. The end of this third period might exist the economical crisis, which so far seems to accept affected mainly intra-European mobility patterns. Peripheral countries have been hit particularly difficult by the crisis, and an increasing trend towards emigration can be observed from countries such equally Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Kingdom of spain. Clearing of non-Eu migrants, however, seems less affected. This is perhaps considering many migrants from outside Europe have found other routes of arrival, including irregular archway and stay. Moreover, European countries are interested in highly skilled migrants in the context of a global competition for talent.

As a result, it seems that comparable to the "migration stop" after the oil crisis of the 1970s or during the Cold War, migration towards Europe will be transformed rather than come up to a consummate halt in the coming years. Mobility within Europe, in this regard, cannot be seen as split up from migration from outside the Eu. Studying migration systems rather than focusing exclusively on one attribute of mobility is thus called for. At the same time, our analyses in this chapter as well suggest an increasing dichotomy between migrants who are in a favourable state of affairs with easy access and rights in Europe (e.grand., European union free movers and highly skilled migrants) and those in less favourable situations (mainly those arriving from exterior Europe for other reasons). Development of this dichotomy has important consequences for the lives of private migrants and for social cohesion. European societies must demonstrate sensation of this with policies crafted to acknowledge the diverse nature and dynamic grapheme of migration that nosotros accept shown in this chapter.

References

-

Abel, G. J. (2010). Estimation of international migration flow tables in Europe. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 173(4), 797–825.

-

Abel, G. J., & Sander, N. (2014). Quantifying global international migration flows. Scientific discipline, 343(6178), 1520–1522.

-

Bade, Chiliad. J. (2003). Europa en movimiento: Las migraciones desde finales del siglo XVIII hasta nuestros días. Barcelona: Crítica.

-

Barou, J. (2006). Europe, terre d'immigration: Flux migratoires et intégration. Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grénoble.

-

Bijwaard, G. (2010). Immigrant migration dynamics model for the Netherlands. Journal of Population Economics, 23(4), 1213–1247.

-

Bonifazi, C. (2008). Evolution of regional patterns of international migration in Europe. In C. Bonifazi, M. Okólski, J. Schoorl, & P. Simon (Eds.), International migration in Europe: New trends and new methods of assay (IMISCOE inquiry, pp. 107–128). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

-

Bonin, H., Eichhorst, W., Florman, C., Okkels Hansen, 1000., Skiöld, 50., Stuhler, J., Tatsiramos, K., Thomasen, H., & Zimmerman, M. F. (2008). Geographic mobility in the Eu: Optimising its economic and social benefits. IZA inquiry written report 19. Bonn: Found for the Study of Labor.

-

Boyle, P., Halfacree, One thousand., & Robinson, V. (1998). Exploring contemporary migration. Essex: Pearson Education Express.

-

Braun, M., & Arsene, C. (2009). The demographics of movers and stayers in the European Union. In E. Recchi & A. Favell (Eds.), Pioneers of European integration: Citizenship and mobility in the EU (pp. 26–51). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

-

Castles, S., Booth, H., & Wallace, T. (1984). Here for good: Western Europe's new ethnic minorities. London: Pluto Press.

-

Castles, S., De Haas, H., & Miller, M. J. (2014). The historic period of migration: International population movements in the modern world. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Quango of the EU. (2002). Seville European Council 21 and 22 June 2002: Presidency conclusions. Brussels: European Commission.

-

De Valk, H. A. G., & Díez Medrano, J. (2014). Guest editorial on meeting and mating across borders: Union formation in the European Union single market place. Population, Infinite and Identify, xx(two), 103–109.

-

Dietz, B. (2006). Aussiedler in Germany: From smooth accommodation to tough integration. In L. Lucassen, D. Feldman, & J. Oltmer (Eds.), Paths of integration: Migrants in Western Europe, 1880–2004 (pp. 116–136). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

-

Dietz, B., & Kaczmarczyk, P. (2008). On the need side of international labour mobility: The structure of the German language labour market as a causal cistron of seasonal Shine migration. In C. Bonifazi, One thousand. Okólski, J. Schoorl, & P. Simon (Eds.), International migration in Europe: New trends and new methods of assay (IMISCOE enquiry, pp. 37–64). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Academy Press.

-

EC. (2011). The global arroyo to migration and mobility. COM(2011) 743 final. Brussels: European Commission.

-

EMN. (2013). Intra-EU mobility of third-country nationals. Brussels: European Migration Network.

-

Eurostat. (2011). Migrants in Europe: A statistical portrait of the outset and second generation. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the Eu.

-

Eurostat. (2014a). Immigration in the European union. Brussels: European Commission.

-

Eurostat. (2014b). Unemployment Statistics. Brussels: European Commission. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained. Accessed 8 Aug 2014.

-

Fassmann, H., & Münz, R. (1992). Patterns and trends of international migration in Western Europe. Population and Evolution Review, 18(3), 457–480.

-

Fassmann, H., & Münz, R. (1994). European East-Westward migration, 1945–1992. International Migration Review, 28(3), 520–538.

-

Favell, A. (2008). Eurostars and Eurocities: Free move and mobility in an integrating Europe. Malden/Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

-

Favell, A., & Recchi, E. (2009). Pioneers of European integration: An introduction. In Due east. Recchi & A. Favell (Eds.), Pioneers of European integration: Citizenship and mobility in the EU (pp. 1–25). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

-

Findlay, A. M. (2011). An assessment of supply and need-size theorizations of international educatee mobility. International Migration, 49(two), 183–200.

-

Fredlund-Blomst, South. (2014). Assessing immigrant integration in Sweden after the May 2013 riots. www.migrationpolicy.org. Accessed 13 Aug 2014.

-

Gilmartin, Thou., & Migge, B. (2015). European migrants in Ireland: Pathways to integration. European Urban and Regional Studies, 22(3), 285–299.

-

Glick Schiller, N., & Salazar, Due north. B. (2013). Regimes of mobility across the world. Periodical of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(two), 183–200.

-

Goldscheider, C., Bernhardt, E., & Goldscheider, F. (2008). What integrates the second generation? Factors affecting family unit transitions to adulthood in Sweden. In C. Bonifazi, M. Okólski, J. Schoorl, & P. Simon (Eds.), International migration in Europe: New trends and new methods of analysis (IMISCOE inquiry, pp. 226–245). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

-

Hansen, R. (2003). Migration to Europe since 1945: Its history and its lessons. The Political Quarterly, 74(s1), 25–38.

-

Hatton, T. (2004). Seeking asylum in Europe. Economic Policy, 19(38), 5–62.

-

Hoerder, D. (2002). Cultures in contact: World migrations in the second millennium. Durham/London: Duke University Press.

-

INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). (2014). Estadística del padrón de Españoles residentes en el extranjero: Datos a 1-1-2014. www.ine.es. Accessed xiv Aug 2014.

-

Kleinepier, T., De Valk, H. A. G., & Van Gaalen, R. (2015). Life paths of Polish migrants in the Netherlands: Timing and sequencing of events. European Periodical of Population, 31(ii), 155–179.

-

Kupiszewska, D., & Nowok, B. (2008). Comparability of statistics on international migration flows in the European union. In J. Raymer & F. Willekens (Eds.), International migration in Europe: Information, models and estimates (pp. 41–71). Chichester: Wiley.

-

Lange, T. (2013). Return migration of foreign students and not-resident tuition fees. Journal of Population Economic science, 26(2), 703–718.

-

Levrau, F., Piqueray, E., Goddeeris, I., & Timmerman, C. (2014). Smooth immigration in Kingdom of belgium since 2004: New dynamics of migration and integration? Ethnicities, fourteen(2), 303–323.

-

Mannheimer, L. (2012). Fler utvandrare än på 1800-talet, Dagens Nyhet. 20 February.

-

Münz, R., & Ulrich, R. (1998). Germany and its immigrants: A socio-demographic analysis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 24(1), 25–56.

-

Murray, R., Harding, D., Angus, T., Gillespie, R., & Arora, H. (2012). Emigration from the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland (Inquiry written report 68). London: Home Function.

-

Nekby, 50. (2006). The emigration of immigrants, render vs onward migration: Bear witness from Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 19(two), 197–226.

-

Nowok, B., Kupiszewska, D., & Poulain, M. (2006). Statistics on international migration flows. In M. Poulain, Northward. Perrin, & A. Singleton (Eds.), THESIM: Towards harmonised European statistics on international migration (pp. 203–231). Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

-

OECD. (2011). International migration outlook 2011. Paris: Organisation for Economical Cooperation and Evolution.

-

OECD. (2013). International migration outlook 2013. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

-

Function for National Statistics. (2011). Migration statistics quarterly report, November 2011. London: Part for National Statistics.

-

Okólski, K. (2012). Transition from emigration to immigration: Is information technology the destiny of modern European societies? In 1000. Okólski (Ed.), European immigrations: Trends, structures and policy implications (IMISCOE research, pp. 23–44). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

-

Folio Moch, L. (2003). Moving Europeans: Migration in Western Europe since 1650. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

-

Pascouau, Y. (2013). Intra-EU mobility: The "second building cake" of European union labour migration policy (Issue paper no. 74). Brussels: European Policy Centre.

-

Penninx, R. (2006). Introduction. In R. Penninx, M. Berger, & One thousand. Kraal (Eds.), The dynamics of international migration and settlement in Europe: A state of the art (IMISCOE articulation studies, pp. 7–17). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

-

Pieke, F., Nyiri, P., Thuno, M., & Ceccagno, A. (2004). Transnational Chinese: Fujianese migrants in Europe. Stanford: Stanford Academy Press.

-

Poulain, Yard., Perrin, Due north., & Singleton, A. (Eds.). (2006). THESIM: Towards harmonised European statistics on international migration. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

-

Raymer, J., De Beer, J., & Van der Erf, R. (2011). Putting the pieces of the puzzle together: Age and sex activity-specific estimates of migration amongst countries in the European union/EFTA, 2002–2007. European Journal of Population, 27(2), 185–215.

-

Ryan, Fifty., & Mulholland, J. (2013). Trading places: French highly skilled migrants negotiating mobility and emplacement in London. Periodical of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(4), 584–600.

-

Santacreu, O., Baldoni, E., & Albert, M. C. (2009). Deciding to move: Migration projects in an integrating Europe. In E. Recchi & A. Favell (Eds.), Pioneers of European integration: Citizenship and mobility in the EU (pp. 52–71). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

-

Tremblay, Grand. (2005). Academic mobility and clearing. Journal of Studies in International Didactics, 9(3), 196–228.

-

UNCHR. (2001). Asylum applications in industrialised countries, 1980–1999. Geneva: United Nations Loftier Commissioner for Refugees.

-

Van Mol, C. (2014). Intra-European student mobility in international higher education circuits: Europe on the move. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Verwiebe, R. (2014). Why do Europeans drift to Berlin? Social-structural differences for Italian, British, French and Polish nationals in the period between 1980 and 2002. International Migration, 52(4), 209–230.

-

Vilar, J. B. (2001). Las emigraciones Españolas a Europa en el siglo 20: Algunas cuestiones a debater. Migraciones & Exilios, 1, 131–160.

Acknowledgments

This inquiry was part of and supported by the European Inquiry Quango Starting Grant project (no. 263829) "Families of Migrant Origin: A Life Course Perspective".Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits whatever noncommercial employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(south) and source are credited.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution-Noncommercial two.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past-nc/2.5/) which permits whatever noncommercial apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work'due south Artistic Eatables license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such cloth is not included in the piece of work's Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted past statutory regulation, users volition need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt, or reproduce the material.

Reprints and Permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 The Writer(due south)

Virtually this chapter

Cite this chapter

Van Mol, C., de Valk, H. (2016). Migration and Immigrants in Europe: A Historical and Demographic Perspective. In: Garcés-Mascareñas, B., Penninx, R. (eds) Integration Processes and Policies in Europe. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21674-4_3

Download commendation

- .RIS

- .ENW

- .BIB

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21674-4_3

-

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

-

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-21673-7

-

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-21674-4

-

eBook Packages: Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Source: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-21674-4_3